It took just days after French farmers took to the streets for Brussels and Paris to backtrack on important green goals.

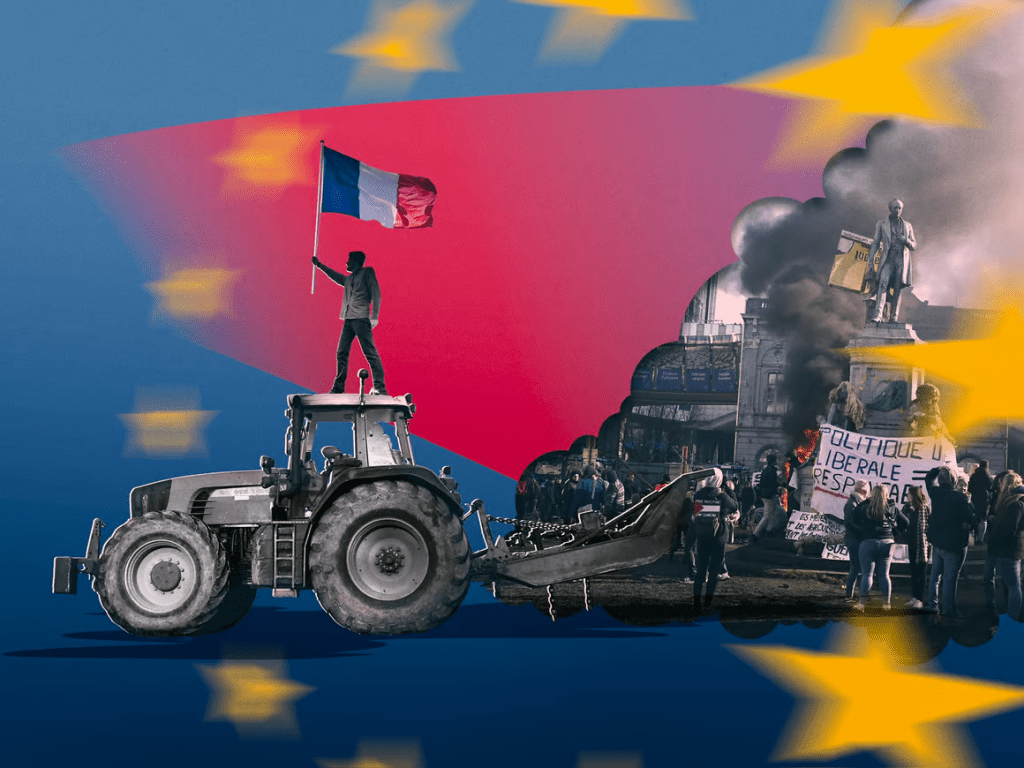

Photo-illustration by Dato Parulava/POLITICO (Source images via Getty Images)

PARIS — Protesting farmer Damien Radet, stationed at a highway roadblock outside Paris, had a blunt message for the politicians who lead France and the European Union.

He demanded a “stop and reversal” of strict EU environmental standards and protection against import competition — including a halt to what he called massive food imports from Ukraine.

“We need more consideration from the state for those who work to feed us,” Radet, a local official from the FNSEA farm union, told POLITICO.

Within days, President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen had folded comprehensively to a group that, in France, makes up just 1.5 percent of the population.

Undoing years of work on her environmental agenda, von der Leyen reversed green farming rules, restricted food imports from Ukraine, and killed a plan to slash pesticide use. With a European election looming, neither Paris nor Brussels dared to pick a fight with farmers prepared to dump Spanish tomatoes on the roads of southern France or mount a raid on a food logistics hub on the outskirts of the capital.

Several EU officials acknowledged that some of the changes directly resulted from the farmers’ protests around the continent.

The same happened in France where, by his own admission, newly-appointed Prime Minister Gabriel Attal gave in to farmers’ demands in a bid to “answer [their] expectations.” He ordered a pause on new pesticide bans, a U-turn on a price hike on tractor fuel, and pledged to go no further than EU law requires on environmental restrictions.

The swift concessions have triggered a backlash from environmentalists, who question how serious von der Leyen and Macron are in their climate commitments. And they beg an important question: If these concessions fail to buy rural peace, what else can they do?

“From a democratic point of view, it is worrying and problematic to see how farmers, who are for sure representative of their category, have managed to monopolize attention and even change the direction that environmental policy is taking in Europe,” said Alberto Alemanno, a professor of EU law at HEC business school.

This move revealed the “weakness” of Macron’s green credentials and could even cause a snowball effect, he warned. “We can wonder which social group will be next to succeed again in ranting — and changing the political priorities of this government.”

And, although farmers in Germany, Poland, Italy and Belgium have also taken to the streets, nowhere have protests around Europe had such direct and immediate political consequences as in France.

Moderate lawmakers from other European countries aren’t impressed.

The Commission and member countries “are relaxing or adjusting green policies for a single reason: we are three months away from the European elections,” said Spanish MEP Jordi Cañas from the Renew Europe Group of which Macron’s own Renaissance party is a member.

Non to Mercosur

There’s more: Macron has escalated his fight against a trade deal that Brussels is trying to conclude with the Latin American Mercosur bloc — frustrating other EU governments that support the creation of a free-trade area spanning nearly 800 million people.

Taking EU trade policy hostage in a bid to placate French farmers — up in arms over future imports of Brazilian beef — isn’t playing well in other EU capitals.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, hosting Attal for talks in Berlin this week, said: “I believe that we all agree that we need such agreements.”

The 34-year-old French premier flatly contradicted Scholz, saying: “We agree to disagree, comme on dit.”

Cañas took a dim view in particular of Macron’s Mercosur playbook: “They are adopting measures that simply seek to defuse tensions, either through cosmetic concessions or by shifting problems to a culprit, as in France’s case with the Mercosur,” he told POLITICO.

The deal is the “perfect villain to project and divert the attention of farmers, as if the sector’s problems would improve by worsening its capacity to export,” said Cañas, who chairs the European Parliament’s delegation for relations with Mercosur and, like the Spanish government, strongly supports the deal.

In the name of bon sens?

Macron was quick to stress that France was not giving up on its green ambitions to please farmers and to insist that he was being pragmatic in relaxing some green rules.

“It is a matter of common sense, we have always been on their (farmers’) side,” Macron told reporters last week in Brussels, stressing that the EU should find the right balance between the green transition and protecting farmers.

The French president was also clear that, if Brussels doesn’t listen to farmers and simplify rules, the far right could triumph at the European election in June.

And, faced with his first political test, Attal stopped at nothing to demonstrate that he shared the concerns of farmers — on farm visits staging press conferences using a bale of hay as a podium. The farmers’ robust protests, which included pouring liquid manure in front of state buildings, received little to no official condemnation.

Even though farmers account for a tiny share of employment and economic output in France, they are skilled in presenting themselves as a “minority speaking in the name of a silent majority,” said Eddy Fougier, a political scientist who specializes in protest movements.

In contrast to the disorganized yellow jacket movement that troubled Macron during his first term, French farmers are strongly led by the powerful FNSEA farm union, and have allies in French institutions, from municipalities to the parliament, explained Fougier.

“The influence of the agricultural world on French politics is palpable,” he said, adding that farmers are increasingly leaning towards Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally. And, despite their small numbers, farmers enjoy the broad support of the French public, opinion polls show.

That explains why Attal has been so quick to bow to most farmers’ demands. The strategy has proved effective in the short term, with unions calling on the protesters to lift the blockades. But they could could weaken politically over the longer term.

The French government is already facing a backlash from environmentalists, furious about the concessions made on pesticide use and dumbfounded by the government’s restraint in policing the protests.

Climate activists would be “sentenced and jailed” if they had done “one thousandth” of what the farmers did, Green party senator and former presidential candidate Yannick Jadot said in a TV interview.

And even some farmer-friendly politicians fear that excessive concessions go against the public interest of EU voters.

“There are voters who might be less noisy and extroverted than the farmers are at the moment, but who are glad we have environmental restrictions to protect fundamental resources like air and water,” said Benoît Biteau, a French Green MEP and a farmer by trade.

Source: Politico